No One Can Say They Have “Favorite” Holocaust Photos. Favorite as a Word Does Not Exist in That World. No, One Only Has Those Which Have Deeply Touched Within, Those in Which We Recognize Ourselves & in Which We Recognize Our Mother, or Brother, Childhood Playmates, or Grandfather, or One’s Own Little Girl or Grandchild, of Which There Should Be Many in These Photos.

***

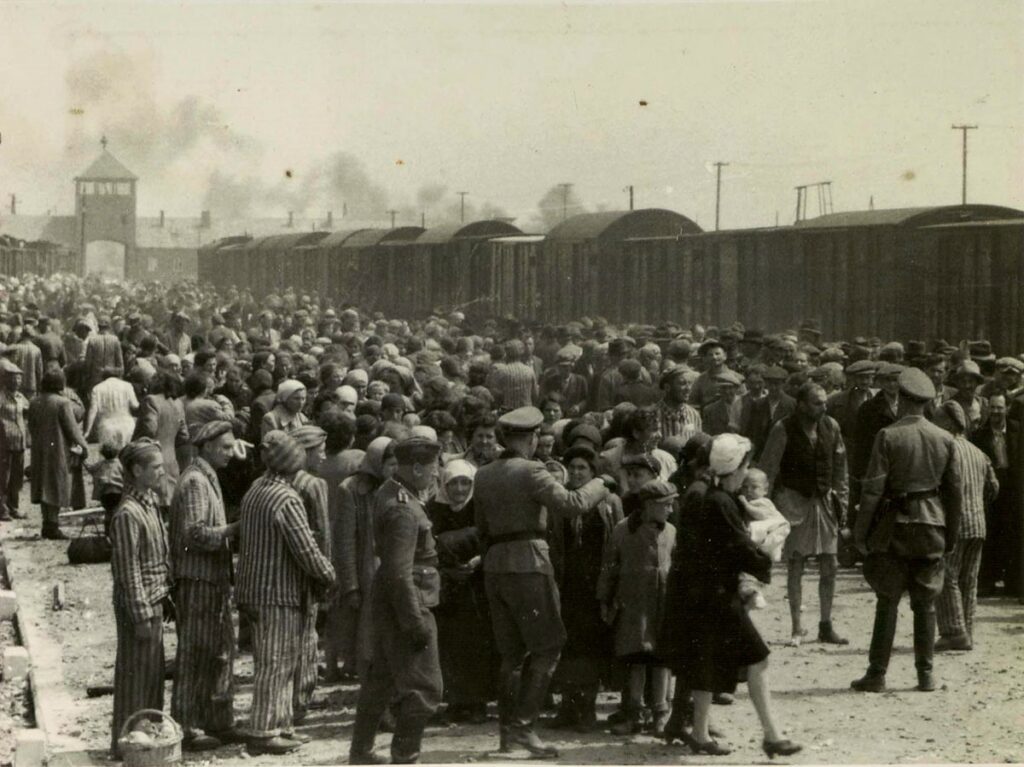

All the photos of this posting, except the last photo, come from “The Holocaust Album”, of which I wrote a book review along with “The Last Album” on May 24, 2022. “The Auschwitz Album” and the photos within it comprise, an official government pictorial report of the processing of a transport of Hungarian Jews – counted as “units” for planning and reporting purposes – that arrived in Auschwitz on Friday, May 26, 1944.

The official German title of this pictorial presentation was “Resettlement of Jews from Hungary”. The photographer(s), not fully identified, obviously had free access to photograph the entire process from the train’s arrival at the platform at Auschwitz/Birkenau, to the complete processing of the various categories to which the arriving men, women, and children were placed during the “Selection” process.

The photographer(s) arranged the photos in the book by description of the process photographed. The descriptions/sections of the photos (which for this post, I numbered 1 -12) are:

1. Arrival of a Transport (3)

2. Selection (3)

3. Men on Arrival (1)

4. Women on Arrival

5. After the Selection, Still-Able-Bodied Men

6. Still-Able-Bodied Women

7. No Longer Able Bodied Men

8. No Longer Able-Bodied Women and Children (3)

9. After Delousing

10. Assignment to Labor Camp

11. Personal Effects

12. Birkenau (6)

The number in parentheses after a description/section is the number of photos used from that section in this post.

I have identified the photos included in this posting by the number of the section in which the photos reside, as designated above, followed by a letter designation as to the order of the photo from the section placed in the text. The cover photo of this post is 8a.

“The Auschwitz Album” does not contain photos of bodies or those inside the gas chambers. No, the truth contained within this book is harder to bear. It is for the most part a photographic essay on the processing of thousands of Hungarian men, women, and children who arrived as “units” by train at Auschwitz/Birkenau on a specific day.

Except for one photo from the album, the front cover photo of this posting, which was taken from behind the woman and her children, you will be looking at the faces, and many times directly into the eyes, of those you may come to recognize and understand as your grandmother or mother, or younger brother or sister, or grandfather and uncles and aunts and cousins, or your own children or grandchildren, and those you just pass on the streets in your neighborhood and town and nod towards in recognition and greeting.

And most of those of whose eyes you look into – especially the mothers and grandmothers and the children, and the grandfathers and other old men bundled along with them – will in less than two hours after being photographed, be gone, if the processing works on schedule and as carefully designed and planned for the units you see before you – the Jews, who had just arrived on a transport from Hungary. In these photos, you are looking upon and into the eyes of men, women, and children, subjects captured in a planned and officially sanctioned photo report, who will be dead and literally ashes before the last photos of these persons are even printed.

And also, we must not forget, in viewing these photos, as we look into the eyes of those persons soon destined for destruction, that the photographer, himself also a human, also looked into the eyes of those he photographed, knowing full-well where each step was leading them closer.

(1a) The train has arrived from Hungary. The cattle cars of the train stretch to the end of the photo, taken from on top of one of the cars. In the foreground, a woman converses with one of the Polish or Jewish prisoners assigned to helping with the offloading of the transports. She seems to smile, but because of the distance from the camera it is hard to tell. Probably as a new arrival, she is asking the prisoner worker what actually happens at this place. It is forbidden for the prisoners to have conversations with the new arrivals except to give directions, and this prisoner would be harshly punished if he was ever caught divulging the full truth of this place called Auschwitz. And, in the middle of the front group, barely visible, an older woman appears to be looking up at the photographer who must be on top of the train car.

To the left of this large front group, near the bottom of the photo, a mother seems to converse or speak to her older son, who has his arm through hers to help her, but perhaps this is his grandmother. The full intent of those offloading from the train were to find and group together with their family, and sometimes with larger extended family.

In front of this woman and boy, there are two young girls holding hands, perhaps sisters, and in front of them, is a woman holding a small child with a boy in front of her. This woman and boy are looking to the left, the boy perhaps at the prisoner worker to his left near the train tracks. and the woman may be looking at the woman next to her who is also holding a child, and the child appears to be trying to get down, as young children often do when they want to walk on their own.

Though also, both the woman and the boy looking left may be looking at the camp across the two sets of railroad tracks just a little in the distance, to the group of men in dark clothing, perhaps soldiers, at the electrified fences and the camp buildings beyond. All this is new and perhaps unsettling.

The prisoner worker to their left – one of the prisoners helping with the offloading and other tasks – is by himself, apart from the larger group of prisoners a little farther ahead – and he does not appear to be talking, but rather he seems to just be looking at the new arrivals, perhaps blankly, for he knows the purpose of this place, and his silence may be deepening his own misery and guilt.

Lastly, in the background on the left, the chimney of the crematoria rises from one of the killing centers, its twin, across the railroad tracks and on the other side of the train to the right, the destination soon for many of the lives captured in this photo.

(1b) In this photo, families are leaving the cattle car they were forced into at some gathering point in Hungary. There are children everywhere, I quickly counted ten. One child is still in the cattle car at the now open door and is being held perhaps by the mother and below it appears as if a sister is waiting to take her with waiting open arms. Tender family love and care has survived the long and difficult trip.

The boy standing in the doorway of the cattle car to the left, appears to be looking at the photographer – perhaps this man and his camera being one of the first things he saw when the door of the cattle car in which he and his family were transported, had opened onto a strange and fearful and noisy place, this place called Auschwitz.

A boy with a hat, is on the ground near the open door of the cattle car – not a young child, but he does not appear to be a teenager – holds his younger sister, and keeps his younger brother, also in a hat, near him. This boy is also looking at the photographer, and looks anxious and wary and perhaps fearful, for many times those tasked with the care of others, here younger siblings, become more attentive and attuned to surroundings, and his face seems to reflect an instinctual need to keep the sister he holds, and his younger brother beside him, safe or at least away from, whatever he sees and senses.

Four young children stand near the door in the right of the photo, the youngest appears to look at the photographer with an expression that displays more than just a simple distrust and fear of strangers. Many of those in these photos, perhaps including this child, may have observed the face and expression of the photographer, before he took the photo. The photographer’s face and expression are something we do not have an image of, but if we did, it would open up the entire world of these photos to a greater understanding. However, even without the face of the photographer, we know from this child’s face, that the mistrust and misgivings upon it were accurate and true. Upon and from the face and eyes of babes!

In the middle foreground of the photo and to the left, two children are held in the arms of women. The women right in the middle seems possibly the grandmother of the one she holds, a little girl, and anxiety and distress is upon her face as she speaks to the man on the left, perhaps with blankets strapped to his back, possibly the father of the child, as he is very attentive to her with direct eye contact.

The woman between them, whose face we do not see, may be the mother or perhaps an older sister of the child she holds, a boy, possibly big for his age, a family member, but nevertheless, a cumbersome weight to hold, which she does to the best of her ability.

Again, within all the confusion and uncertainty of being in a place of unknown threats and fears, families instinctually are anxious to be and stay together and fear being separated, especially in a place of where they do not know what awaits them.

(1c) And now with this photo, the families are not together, the grandfathers, fathers and older brothers and uncles and male cousins and other men have been separated into a different column.

In this photo, I quickly count fifteen faces and the backs of the heads of children. Most of the children now look uneasy and anxious and wary as do some of the women, though a few smile, possibly thinking the photographer is taking welcome photos.

The boy in the foreground to the left, the star of David prominent upon his jacket, seems deeply sad as if with what he sees there is nothing to lift his spirit or settle his fears. He may not be looking directly at the photographer but slightly down, whereas the two girls behind him, perhaps his sisters, look directly at the photographer, with wariness and some fear upon their faces, but perhaps feeling a bit safer having their brother between them and what they see, especially now that their father is no longer with them.

The woman near the center in the dark coat and scarf reminds me very much of one of my Cub Scout den mothers when I was a boy, who was kind and always unflustered with our antics, and with who for Easter, we made Easter candy crosses out of snicker bars, decorating them with different colored icings squeezed out of tubes.

People are not really all that different from whatever we conceive “us” to be.

(2a) These next two photos taken just moments apart, show the women and children during the selection process, where those selected for work would be sent to the left, and those not selected for work were sent to the right.

In this photo, a woman holding a very young child is going to the right and behind her, the selection process involving two boys with caps is just beginning. The German officer in charge of the selection, appears to be pointing to the older brother in the cap, but is engaged in a conversation not of his choosing with the boy’s mother. The boys’ mother, closer to the officer, appears very actively engaged in whatever conversation is going on, and the boy looks apprehensive and stressed and appears trying to understand what is being said about and to him, but obviously wanting to stay with his mother and younger siblings. A second German soldier alert to the situation begins to move towards the boy.

To the left of this photo are four probably Jewish prisoners stationed to do whatever they are ordered to do to quietly and quickly facilitate the selection process. One appears very young, perhaps a late teenager or early 20’s, and he appears to be watching the selection of the older brother in the cap. Perhaps the scenario playing out before him is very similar to his own selection, and he may identify with the newly arrived Hungarian boy. He appears empathetically concerned, as he knows the mother and boy may unwittily have initiated a dangerous losing game, he but remains immobile.

At the feet of this young prisoner, sits what appears to be a basket of fruit, probably confiscated from a woman unwilling to leave it behind at the point of where she and her family were offloaded from the train, having already had to leave all the other possessions she had brought for her family which they were told would be taken to the family camp they were to be assigned and available for retrieval after they were completely processed. When the fruit was taken, she and her family must have instantly regretted they had not already eaten the fruit, probably saving it to eat at a later time, but how were they to know…

Another confiscated travel bag appears not too far in the distance behind him, and a little beyond the bag is a woman with her back to the camera holding the hand of her young child, in conversation with two prisoner workers.

In the middle of the photo, looking at the photographer between two German soldiers, is an older woman with a white shawl.

To the right, with a German soldier and prisoner in front stopping him, is a man in a dark vest without pants and only one shoe who appears to have gotten out of line or perhaps been singled out for greater scrutiny. Perhaps the journey in the cattle car has mentally unhinged him.

In the background of the photo to the left, is the tower gate to Auschwitz/Birkenau that the train passed through and under to bring its Jewish cargo to the platform.

(2b) In this photo, apparently taken a few moments after the one described above, now shows to the right the older woman with the white shawl and only the younger of the two brothers in caps with probably the brothers’ mother in between them, and possibly a sister with a white head covering behind them, for as they all walk, they all peer left, probably trying to see where the older brother was directed.

This is the last time they will see the older boy – grandson, son, and brother – for they are being sent in the opposite direction to their right, and if the older boy glances back at them, even if he survives Auschwitz, this will have been the last opportunity for him to see them – his grandmother, mother and younger brother and sister – for in a couple of hours these members of his family will be gone. Perhaps he will be able to find his father among the able-bodied-men.

Also going right, is the woman behind them with three children, with one girl also peering left but also down, possibly at the soldier’s hand which is directing them, as her sister also appears to do on the other side of their mother, who carries their much younger brother with her right arm.

The man in the dark vest now appears in the middle of the photo accompanied by one of the prisoner workers. He must have caused some type of a fuss or commotion, as many of the men in the column of men are looking towards him.

One of the functions of the prisoner workers was to help keep trouble and agitation to a minimum and keep everything calm and moving along during the selection process. The man in the dark vest seems to have been publicly handled gently with a minimum of force so as not to unnecessarily upset or cause greater agitation among the thousands being processed. The Germans and prisoner workers appear to have been successful here in that endeavor.

The young prisoner is now with his fellow prisoners but now on the far side of the group, looking to help take care of a possible issue with one of the women in the column for selection. The backet of fruit is still where it was.

One of the four prisoners in the group, the tallest one, has moved into the column of women, and appears to be talking to one of them. He has something in his hand, or he may even be touching the outer sleeve of the woman, who appears more urban and better dressed than the women with scarves upon their heads. He appears kind, which may be part of the necessary charade, but he also looks concerned, as do the other prisoners in the group, so probably more likely he is trying to be as kind as he can be under the circumstances they all are in, and perhaps he is also trying to impart something of value to the woman.

In the narratives of some of the survivors of Auschwitz, they mention that sometimes the Jewish prisoners advised women carrying a child who was not their own, to give the child back to its mother, thus trying to save at least one woman from going to the killing center and destruction when she need not.

(2c) This woman, healthy and strong looking, was obviously sent to the line of those selected for work. As she walks, she glances to the line of women and children she just left, to see what was happening to those of her family, to see where they were directed. The expression on her face is one of concern and anxiety, being now in an unknown and dangerous situation where she and other family members have no control. By the way she is dressed and her hair not covered by a scarf, she seems to be from a more urban environment and the woman who follows her.

The man to the right of the woman glancing back, who is in the line of men waiting for the gesture to go to the right or the left, appears to be alone without male family members around him. He may be looking at the photographer, or he may also be looking in the same direction as the woman, towards the line of women and children also awaiting selection, perhaps trying to see if he can spot his elderly mother or his wife and perhaps children in the line, or any other women from his town he may recognize. Perhaps he has already seen his wife and others directed in the opposite direction than the women who pass in front of him, and his look may be one of a quiet concern trying to determine what the difference of direction means for those disappearing in the distance.

The man at the front of the line being examined by the German official, may be too old to be assigned to work, especially in contrast to the much younger man behind him, the contrast even stronger for the man behind the man peering towards his left or at the photographer.

Behind this group of men and the two women passing in front of them, in the distance, appears a column of women with children – a few heads of the children being carried visible. These not-selected-for-work women and the children are already headed for the killing center, with perhaps a German soldier standing near the visible front of the line, to keep the women and children moving along at a steady pace, and to help maintain the facade of calmness with promises of water and assignment to the family camps after the showers – all necessary components of an orderly and efficient processing system of humans – counted as units for planning and reporting purposes.

(3a) In this photo, a father and a son waiting in the men’s selection line, glance back towards the line of women and children, the boy by what he sees, deeply sad and emptied, more concerned and focused on his mother and perhaps brothers and sisters younger than himself, who may at that moment be moving away in another direction, soon to be lost to his sight and to him among the thousands being processed. The father is also concerned, though perhaps more analytical about the situation than his son.

The separation of the men from the women and children, and then the separation of the women selected for work from the rest of the women and children, was the first and perhaps the greatest, longest lasting, and most destructive blow to the mind and soul of so many within these transports. In many narratives, the survivors of Auschwitz and other camps after many decades, are still barely able to speak through their tears and weeping of those whom they were separated from and never saw again.

This photo as a whole shows a complete mixture of the men awaiting selection. The boy in this photo is the youngest, and there are also two partially seen young men, but there are more middle-aged men in the photo, and two or three men who appear to be old.

The father and the son may or may not be selected for work, or one may be chosen and not the other, causing yet another separation. Those arriving at Auschwitz for processing, had no choice, no say, and no knowledge of what any decision concerning them meant.

(8a) This photo is the first from the “No Longer Able-Bodied Women and Children ” section and is the same photo as the cover photo of this posting.

I picked this photo for the cover as it defined and was evocative of the darkness and evil against Jewish men, women, and children that had been meticulously planned by German government officials, and engineers and architects. And with this photo, we see all that planning in operation against this small group led by a woman and I count four children, for there appears in front of the woman a tiny head and a little hand of a child clutching her scarf.

For to me, this woman could be a grandmother bent with age, but she seems more youthful, more a mother who would never part from her children, bending with the weight of a baby she carries in front of her and the stooping down to take the hand of the small one to calm the child’s fears and her own. The child’s older brother has the little one’s other hand.

Her oldest follows her, perhaps more aware of the surroundings than her younger siblings, or perhaps just tired and sad yet determined by habit to keep her steps up to stay with her mother and younger siblings, the only persons left in her life at that moment. For she does not want to be alone, just as she does not want to be here, but rather still at home where she was safe and happy. And where is papa? She already misses him so. If he was with them, her hand would be in his, and that would be so much better. But here she is walking alone.

This photo is one of the easiest in which to see children that we know or have known. For we just add the faces and names onto the little children.

This little family group – the mother and her four precious children – will be ashes in much less than two hours, if production can keep on schedule. This truly happened.

(8b) This photo is the second from the “No Longer Able-Bodied Women and Children” section and shows a group comprised of more children than women. Counting all the children’s faces and backs of heads and in one case just the little shoes of a boy, there appears twelve children in this photo, and perhaps seven women. The children instinctively it seems stay near their mothers and with their siblings.

In the front row, to the left, a mother and her daughter hold hands, and next to them, a brother and sister appear also to hold hands. They all appear to be one family. The girl to the left of her brother, does not look at the photographer but down and to the side, perhaps a little shy, a look I have often seen on one of my granddaughters when she is thinking of something to say or not to say depending on her mood, who now is about the same age as this girl in the photo, and who even looks as if she could be a sister to this shy one.

I love my granddaughter, and I cannot imagine a father who loves his children would not have a special protective place in his heart for a daughter who is always a little shy. But her father is not here, and perhaps his shy daughter is wishing over and over that he was with her, to protect her as he always has.

Behind the boy and girl, a mother stands, holding her son, who is perhaps a little over two. The child does not appear happy, neither does his mother, maybe both are tired, and the boy maybe just a step or two away from becoming absolutely unreasonable, as only a tired and probably thirsty and hungry two-year-old can become.

In the middle right, a boy, about twelve or thirteen, stands in front of his mother it seems, holding in his left-hand a large bag with perhaps food items judging from the round bulging shapes here and there, or perhaps shoes, or actually it could be anything his mother deemed necessary to bring on their “resettlement” journey. In his right hand he holds a smaller bag and also what appears to be something like a briefcase. It is wonderful to have such a helpful, dutiful son in a situation like this. Perhaps at his mother’s directions, he dressed entirely in dark clothes winter clothes complete with a dark cap upon his head for warmth for his family’s journey into the unknown, and the only bright spot upon him is his yellow Star of David – as required.

And this boy, unlike all the others in this photo who are facing and/or looking at the photographer or something in the distance, this boy looks left through the family groups to the electrified fence not far from them, something he probably has never seen before and may not even know what it is now. But more probable, because of the intenseness and apprehension within his gaze, it is probably some sight beyond the fence that has riveted his eyes and mind. Something startling and new and fear producing.

I identify with this boy and see myself within him, as I would have wanted to stay with my mother when I was the age of this boy. As an adolescent, I enjoyed the few opportunities I had to be just by myself with my mom without any of my five sisters, and I always liked going grocery shopping with my mom on Saturday mornings and then carrying the bags of groceries into the house for her. And, also from a very young age, I was always alert to my surroundings and picked up quickly on things that seemed different or strange, as this boy seems to have done in this photo.

I also knew that as a boy small for my age, there was nothing I could do to physically defend my mom or myself from harm. Perhaps this boy now in Auschwitz, a place he had nothing to compare it to, was also just beginning to understand this by what he was seeing and beginning to experience. When a boy this age begins to understand absolute vulnerability, it is frightening and numbing and catastrophic, and his face registers the first inkling of this awful truth.

Between this boy and the two girls on the far right, in the back of the group, is a young girl, and next to her the shoes of perhaps her younger brother. The girl looks directly at the photographer, the little boy doesn’t even see him.

On the far right appear to be two sisters, and they are not looking at the photographer but at something behind him and up ahead. None of the children in this photo seem happy or at ease, and these two girls seem apprehensive and taken aback, and troubled by what they see in front of them perhaps in the near distance.

But how are we now to gauge the level of fear and trepidation that these families, these children, these two girls, experienced in their last hours of life? Here, whatever is ahead, is something that not even the presence of a photographer draws their eyes away from. And the expression on these girls’ faces, and the apprehension on the face of the boy looking left next to them, indicate that now multiple events and things seen and heard are beginning to swirl around and upon the children, producing a vista within them filled with anxiety and apprehension.

Of these two girls, the girl on the far right reminds me so much of another of my granddaughters when she was younger, who at times would just stop when we were at a park or garden and critically appraise some object or something I was asking her to do, who even at the age of two-and-a-half would scowl and cross her arms to indicate that she was not pleased with what she saw and was not going to continue on or cooperate – I have photographic proof. I love this granddaughter, now a teenager, for what she has grown into and become, something these two girls, daughters and perhaps granddaughters, never had the opportunity to experience at an older age – this photo is photographic proof.

This photo is the last of this group of mothers and children, for they will be processed within less than two hours.

(8c) The woman with the glasses and the white shawl looking squarely at the photographer, has always impressed me as a thinking woman, a woman who may not know the exact details, but was acutely aware that something harmful was waiting in the wings.

She is not cowed, she does not express fear, but rather she radiates strength and determination and is someone who will look the photographer of this horror place in the eye. There are other women and children all around her, yet she stands out in the photo as a rock. Maybe one or some of the women are her daughters, and some of the children her grandchildren, and if they are, she’s exactly where she wants to be. And even if none are her children or grandchildren, she will still maintain her dignity and lend her strength for all those around her to the end, or to the beginning of something of which she at this point she knows nothing. This is a marvelous portrait of this woman.

And next to this photo in “The Auschwitz Album”, is a full-page text concerning the building in the background. I quote two paragraphs of the longer piece.

“The building in the background might be mistaken for an administrative center or a dining hall, but behind the double windows are fifteen high-speed ovens, vented through the massive central chimney. Extending underground from the west end of the building (killing facility No. 2), are the dressing room and the gas chamber. Automatic elevators brought the fresh corpses up to the crematory level. Also on this level was a smelter room, where the extracted dental gold and silver were processed into ingots.”

“Except for photographs made during construction, this is the only picture clearly showing either of the great killing facilities that flanked the ramp. No. 2 was dismantled and destroyed, with the other three facilities, in late November 1944, just nineteen months after it went “on line.” “

And this courageous woman of dignity, and the five other women in this photo, and the seven children that I count – boys and girls, three held in the arms of their mothers – will soon be processed after this photo was taken, and they will all be the “fresh corpses” the automatic elevators bring up to the crematory level.

This is the reality of what really happened – over and over – and with these photos we are looking into the faces of those counted as units – families, mothers, children, brothers and sisters – and processed down into ash within the killing facility, the structure standing just behind them.

(12a) Here is the first photo of a gathering of humanity at Birkenau. Birkenau is German for “Birch Grove”, a name evocative of a cool shady place to rest and seek refreshment. And Birkenau – sometimes parts of it referred to as the “waiting room” by surviving inmates – was in fact the place of rest for some of those waiting outside the killing facility, all ignorant of what was beside them and what it meant for them.

The group of this photo is comprised of children and women, mostly mothers and older women not selected for work, but now they are joined by the older men and boys also not selected for work.

In the left middle of the photo, we see two women looking at something or perhaps someone in the distance, perhaps trying to understand an event or determining if a person in the distance is one of the loved ones they were separated from. They look tired. But this is a time of rest, as they are no longer within the cattle cars and walking to this destination, and there does seem a certain degree of relief and rest and a lessening of the tension and fears the people felt along the way.

In the center foreground, with his back to the camera, we see a handsome young teenage boy from what we can see of him, a youth not selected from the line of men for work, sitting next to his mother, perhaps once separated from her, but now happy that he found her among the throng to be with again. For us humans, it is always good and better to be again with family during times of uncertainly, stress and danger. None of us really want to be alone.

And to the left of the photo, we see a grandfather sitting near his two granddaughters, and one of the girls appears to be looking at the photographer. And on the right side of the photo, one young very cute dark-haired boy, perhaps four or so, is also looking at the photographer and smiling, perhaps associating a photographer and photos with birthday parties, or with the holidays, or a week at a lake with his family in the summer.

He looks a lot like one of my young grandsons. And this boy seems so full of life and fun, probably having experienced only love and affection from his parents and grandparents and all those within his family over the few years of his wonderful life. Yes, a boy of joy, and one who was a joy.

(12b) This is another photo of a group of multiple families with many children waiting at Birkenau. One boy standing in the upper middle of the photo, gazes at the photographer with a calm, slightly wary, wondering gaze. The little girl in the right lower corner, well taken care of and embraced by her mother’s protective arms, gazes out to the right, not at anything that delights her, but at something that has deserved her attention and scrutiny and of which she is not sure of its intent. In her hands, she protectively holds something seemingly of cloth and soft for comfort and reassurance, perhaps a stuffed animal, something from home and of happier more pleasant days.

But this photo also contains one of the most poignant scenes of all the photos in this posting. For in the center left, at the farther edge of a small clearing of grass that no one is sitting upon, a small child, perhaps a boy, amidst all of the mass of people around him, has somehow found or been given an object of beauty and interest, a pretty spring wildflower of late May, that he shows to the children across from him to share his pure child’s delight and joy in this beautiful flower of the field.

The two boys opposite him seem surprised but also paused in their actions and thoughts and they are taken, for at least a moment, by the younger child’s object of beauty and perhaps by his happy delight.

The woman to the left of the boys is problematic to interpret for she scowls, but perhaps she is looking at the photographer, or was scowling at something else. And the girl in profile in the center foreground also seems to be looking at something in her hand, perhaps something of interest or beauty she also found among the grass. Even in profile, she looks a lot like my mom in the photos we have of her as a child in London before the war.

But the child with the flower in his outstretched hand has provided a spot of light and comfort and joy to the two boys and to all others around him being processed with him, who saw and were responsive to his act of joy. For even small acts of young children, even within catastrophic evil and horrors, can be a blessing upon those of the moment, and upon those, like us, who now view this small sacred act from this sacred book and take it deeply within us as an act of remembrance and commitment to life.

(12c) This photo, also of those waiting at Birkenau, shows at least ten, possibly eleven children looking at the photographer, as if the photographer had shouted something like, “Children, look here” or something similar, that had attracted their ears and attention, for only one adult it seems is looking at the photographer, the women in the left center, in a black shawl who looks the directly at him.

There is no apparent agitation or anxiety in this photo, but not all is well, as the boy on the far right seems distressed and maybe about to shout out or cry. Perhaps someone he relies on has moved a little too far away.

In the center left of the photo, there is a group, probably a family group, that is clothed in much lighter colors and perhaps more expensive clothes than most of the other children and adults in this photo. In the middle to the left of this group, a boy and a girl in their early teens, stare at the photographer, and they appear to be sister and brother, perhaps twins, or the sister a year older or so, and on the left side of this group, a younger boy similarly dressed, with similar features, also stares at the photographer. Behind the young boy, a well-dressed mother or a grandmother holds a little one who indeed is very precious to her. Her look and gentle smile are of a quiet adoration for the small child, actually just a baby.

Soon undressed and naked, this family group will be the same with all the others, sharing all together the final processing prepared but hidden from them all.

To the right of the woman adoring the baby, a boy in dark clothing appears to be squatting, as if taking no chances, ready for any contingency, and stares at the photographer with mistrust and deep wariness.

I identify with this boy, and with any other boy with his expression, as that is the way I would have been, and was as a child, never entirely comfortable in new or changing circumstances, and never entirely sure of what strangers or persons who were acting different were capable of doing. I would have been watchful and defensive while in Auschwitz, and I wonder if I would have been terribly surprised when I was gassed.

The boy and the girl in the left lower corner also seem brother and sister, and the girl has a box, a container of sorts, that may be filled with paper and colored pencils and a few favorite books and other treasures of her life, which if I was one of these children, I would have also attempted to take, hoping to still pursue my joy and escape in books and in paper to write on wherever I was taken. This brother and sister sit next to a woman, who is probably their mother, and on the other side of their mother, another sister waits with them, but with her back to the camera. She seems to be dressed in one of the little sailor outfits that I even remember seeing as a child on others.

(12d) In this photo, also from Birkenau, three sitting boys along the top of the photo look at the photographer, who somehow has attracted their attention but not the interest of the others in this photo, and he must be standing near and looking down on them with his camera, for the boys are looking up.

Two of the boys, very similar looking and dressed, are brothers, and the third boy, on the right, seems from a different family, but he is facing the same way as the middle boy, so he may have a connection to the family group of the two brothers.

The brothers express a mixture of wary interest but not fear, and the boy who is not a brother, just looks blankly at the photographer, showing no emotion, as if carefully evaluating something not quiet threatening but new and unknown and moving about freely within a place they are confined within – for this boy, it is like trying to understand and play a game hidden from view and without knowing the stakes and the penalties for losing.

The rest of this group is looking towards the girl to the left who seems afraid of something that she is trying to ward off. On the face of the woman and the boy in the middle right, there seems amusement as if the girl is merely trying to ward off a bug or something that she is not familiar with. Perhaps a bee?

The expressions of the girls along the bottom front of the photo we cannot see, but overall, it seems we can assume that whatever the girl is trying to ward off, it is just strange and bothersome, and her distress a source of amusement and interest to some and probably having nothing to do with the work schedule and processes of Auschwitz, which would have been a shared concern of all.

And returning to the boys, it is with an ever-deepening emptiness that I understand and know that the two brothers, poised and confident, and the third boy, perhaps more reserved, will be gassed and will perish together, and that their fresh naked corpses will ride the elevator up to the crematoria also together to be reduced to ash, within an hour or so of when this photo was taken. This is a reality hard for me to internalize and accept as real, though a reality it is, and a reality it was for these boys, who had done nothing wrong but had been born Jewish.

(12e) In this photo, also from the Birkenau section, the woman and children and no longer able-bodied men, seemed to have been given the invitation, or order, to get up and gather their belongings as soon they will be moving towards the “showers” and many times hopefully towards a long-awaited promised drink of water.

In this photo, most the people are already up, though in the foreground of this photo there is still a small group of people sitting down, and farther back from them, one man still sitting, is looking to the left as if that is where the order or the commotion is coming from.

On the far right, the woman standing is also looking towards the left, her expression one of evaluation and uncertainty. Perhaps she is also finishing eating some of the food she had prepared long days ago for her family’s journey then into the unknown, eating now at a place of even greater unknowns.

The boy on the left, maybe twelve, is putting his heavier outer coat on in preparation for moving to someplace else, and the expression on his face, seems one of pain as if the act of putting arm into sleeve is painful. But more probable, the act of putting his coat on now speaks deeply to the confusion and anxiety he has felt since being separated from his father, and not knowing where the next steps will actually bring them. His sister next to him seems utterly exhausted and barely able to keep her eyes open, for she is so tired from the entire journey which has been so long and wearying from when she left her home for the last time days ago, too tired now to even think or consider any about where she is going or what is next.

In the middle of this photo, five look directly at the photographer, one woman, two older girls who seem sisters right in the middle, and then to the right, two younger girls dressed in lighter clothing, who also seem to be sisters. How the photographer managed to attract their attention and have them look at him, we do not know, and we will never know. And upon all their faces seems a common thread of tiredness.

The woman on the left of the sitting group definitely looks tired. The younger of the two sisters in dark clothing is already standing up and seems more alert than her mother and older sister still sitting. She quietly observes the photographer with traces of an enthusiasm for life so common in the hearts of young teenage girls. In the photo she is not smiling, but perhaps in a moment she may have.

Her older sister, still sitting, turning her head to view whatever attracted her sister, has an open expression of fear – the eyes that we possess, by which we behold, always the most expressive part of our face, the windows into our being.

Of the two little girls in the foreground, the one on the left sitting down with a bow in her hair, carefully placed there by her mother for the journey, has no expression that we can characterize other than that she seems tired and just wants to rest, and what she really wants is what she will not be given, and that is just to go home.

The other little girl standing holding her hands together – is for me the true focal point of this photo. For all of my daughters, and all of my granddaughters, have been at this age – perhaps four or so – and she appears stately, elegant even. She also, like her sister with her, has a bow that her mother lovingly crowned her head with as they parted from their home. But the expression on her face, when we begin to study it, begins to haunt, for she appears to be on the verge of tears with eyes as if pleading for something, perhaps rescue, though she may not even have known that word.

For she is staring at the photographer, and whatever her eyes pleaded from him was not realized, but now with this photo, her eyes continue to also stare and plead for something from us, not rescue of course, as she was gone soon after this photo was taken, as was the ribbon from her hair.

But her eyes still plead for the only one thing they can – for us to remember that she was just a child of about four, who once lived and had a mother who loved her and placed ribbons for a journey upon her hair. She now pleads that we should not forget her, and that we should raise our voices while we still have breath and our own eyes to see and understand, so that this will never happen again to any child, to any little girl, with or without ribbons in her hair.

This photo is also one of the photos I have selected that I will have printed and put in a frame to place on my desk to always remind me of what I have seen and understood as I have journeyed through this book – all summed up and now confronting me from the face of a little girl, especially her eyes.

(12f) This is the last photo taken for this post from the section designated as Birkenau. And it is the most holy of all the holy photos of this holy book and the photo most difficult for me to write about.

This photo, because of its placement as one of the last in the Birkenau section, is of a group that is now approaching the gate of the killing facility. And this photo is also unique, in that to my knowledge, it is the only photo where individuals have been identified by name – Aunt Yolan Hylan, Irvin, 8, Dore, 10, Udik, 6, and Naomi, 2.

I believe Aunt Yolan is the woman to the left staring at the photographer, radiating anger and resentment towards him, and who is holding Naomi, the only two-year-old in the photo. The other named children must be the three children beside and slightly in front of her. The boys in the foreground are Irvin and Dore – Dore being a Hungarian name for a boy – the girl hidden behind and between them except for her face, must be Udik. The hand of the boy at the front of the three children, is held within both hands of the woman beside him, perhaps also a relative. The woman meditatively looks down, perhaps in prayer.

Arriving at this end point of the group’s path through Auschwitz – starting from the off-loading from the cattle cars at the train ramp, through the selection process, to their long walk to Birkenau, to their wait among the trees and grass, to their now entering the killing facility – has indeed been a long, long journey.

The only bright spot, if you will, in this photo is the well-dressed young woman or older girl partially seen on the far right, who smiles at the photographer, perhaps still thinking the best, unable, from the love that has surrounded the circumstances of her life, to imagine any awful harm befalling them, the photographer proof of the intended good, for why would anyone photograph others to be harmed, especially one as loved and happy as she. The knowledge or imagination of such evil does not dwell within her.

However, all of the other persons in this photo, adults and children, and even two-year-old Naomi, look apprehensive, fearful, anxious, or numb, except Aunt Yolan, who looking directly at the photographer, glowers with anger and animosity towards him – the photographer who, with whatever intent and emotions within him, has followed the industrial processing of these Jews everywhere along the planned path of evil, the Jews who arrived on the transport from Hungary on Friday, May 26, 1944. And the photographer now records for the pictorial report, the last moments of this group before their entrance into the final processing step within the killing center – the final solution of reducing them all to ash – meticulously prepared and engineered by the German Nazis for them and millions of other Jews

In this photo, I profoundly identify with the taller of the two boys, perhaps Irvin, who is now fearful, through what he has seen and experienced along this path to destruction, and now also by what he sees or perceives to be in front of him. Irvin is just a boy of ten, and a deep hollow fear has expanded within him at this final place, where all is unknown to him, but where what awaits him, is clinically deadly and magnified evil and cruel.

And Irvin is without his father – without his hand, without his protection, without any part of him – perhaps now even without remembrance of him, as gnawing pervasive fear banishes all within, except the fear itself. This emotion has so captured him, that unlike the other boy, Dore, Irvin does not look at the photographer, because for him, deep apprehension and fear have already overwhelmed him.

I recognize – we all recognize – the expression on Irvin’s face, and we know that he, and all of those within this photo, will soon experience something far beyond what is feared or imagined now within this boy. And of all the people within this photo, perhaps it is just Irvin and glowering Aunt Yolan who have now begun to know and understand, at some level within the broad spectrum of thought and emotion expressed upon their faces, why they have been brought here, even if still they do not know the details.

Udik, the six-year-old girl, seen between Irvin and Dore, looks directly towards the photographer with a haunting gaze – sad, apprehensive, filled with uncertainty – all expressed on the face and in the eyes of such a beautiful little girl in one of her last passing moments. Hopefully Irvin is holding her small hand.

But the deepest trauma for me with this photo, and why it was so difficult for me to gaze upon this photo at length and write of it, is because of Naomi, the two-year-old held in her mother’s arms, who now beholds or senses something so troubling, something so riveting, that her face reflects the fearful things she beholds and she is almost on the verge of tears.

And what deeply troubles me with her, is that she looks so much like my youngest granddaughter, who even now as I write this is not far in age from her. And it is this photo and this child, Naomi, and the expression on her face which was the terrible genesis urging me to imagine and write this entire post.

For once we see ourselves or our lives, or even more, once we recognize someone we love – such as a small child we have held and kissed and been blessed by their tiny hands upon our face and their laughter – then, and only then, I believe, can we experience compassion deep enough within us to then extend to others – to our neighbors, to strangers – the compassion we have learned, and true concern and care for them, just because they are persons, unique individuals created in the image and likeness of God, to whom, yes, we have a duty to love and to protect to the best of our ability, even in such difficult times as the Holocaust, as indeed some did, even if it means picking them up and holding them in our arms and walking with them to and through a place of horror without us knowing all the details of what lays ahead.

(To view another posting where I write of the granddaughter that Naomi so reminds me of, please see the link below at the end of this posting.)

This photo is not from the Auschwitz Album but from the book, “Lódź Ghetto – Inside A Community Under Siege” – complied and edited by Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides. This photo has always haunted me because the young man carrying his young daughter looks a lot like me when at his age I had our own precious first-born daughter.

Since the father in the photo has wrapped his daughter in a cozy furry coat to keep her warm, and he and others are carrying bundles of belongings, the two women to the left particularly burdened, this photo may record the arrival of Jews deported from the Reich in October and November 1941 to Lódź, Poland, a deportation always considered by the German authorities as an interim step towards implementing the final solution upon all the Jews forced into the ghetto.

Just as this father carries his daughter, I remember best carrying my first-born daughter like this before there were two and then three daughters to juggle and move along. And every time I would pick up my first-born, I always felt a deepening love for her, as my oldest did not have much need for or interest in other people – she didn’t smile for my mom for two years – but she loved her daddy, and her daddy fantastically loved her. And the father in this photo was probably not much different than me in his love for his daughter, perhaps his first and only child, who he now carries into the Lódź ghetto – dilapidated, overwhelming crowded, and always desperately hungry.

In this photo, both the father and his young daughter – whose names we will never know – reflect an uncertainty and deep unease, and every time I see this photo, it touches me deeply, for I feel within me what may be troubling and growing within him – an anxiety and a gnawing painful confusion of not knowing into what he is carrying the one most precious in life to him, perhaps all multiplied by the realization that nothing here is within his control, and that there is nothing he can do about anything within this place that he knows nothing about.

For within the Lódź ghetto, in addition to hunger, he will only find unconfirmed rumors and baseless hopes about his life and the life of his daughter. And however short or long their stay in Lódź, it will certainly conclude with the enforced separation and death of the precious daughter now in his arms, and most probably also his own death after her in time, a time for him only lived in grief and despair and deepening physical hunger.

***

Postscript

I acquired “The Auschwitz Album” many years ago and I read every word of the book and lingered over every photo, and even then, I gravitated more towards the photos of the transport’s arrival and the photos portraying women and children, because those photos focused most clearly on people as individual persons, especially the children.

In preparing to write this posting, I selected sixteen photos out of the more than 180 photos within “The Auschwitz Album”, principally from four sections – Arrival of a Transport, Selection, No Longer Able-Bodied Women and Children, and Birkenau, to primarily focus on the columns and groups of women and children, and individual children within them.

For ever since I first purchased and read this book, I’ve always treated it with reverence, as I knew the photos were such an important and unique recordation of a greatly horrific evil, and that the book itself, was miraculously found and preserved. Since purchase, I have kept it among the books I keep on my nightstand. I have never lent it out and I never will. And now, I occasionally consider who among my grandchildren would I want to have the book when I am gone, who would treasure its pages and the photos and the history and especially the truth, the difficult truth, they record.

It was with this same attitude of reverence that I approached the preparation for and the writing of this post, always aware that I was writing something that I absolutely needed and wanted to get right – right for me being essentially that I gave, to those I wrote of, breath, voice, and life. For the persons within The Auschwitz Album – for this post mainly the women and children, but also a few men – were once living human beings created in the image and likeness of God – many of the children just of very few years – whose lives were systematically, horrifically, and murderously taken from them.

And it was easy to create – actually from my perspective, recreate – the voices and stories of some of the children, for I identified closely with some of the boys because of the expressions on their faces, and I ached for many of the girls because they reminded me so much of my own daughters and granddaughters, which together birthed a deep emotional journey within me for these children, painful at times, but necessary to give them breath and life and voice for my readers. Blessing these children with life and voice was perhaps the clearest goal I came to have in writing this post.

***

There are really no last words for this posting, just as there are no favorite Holocaust photos, but perhaps the most important thing we can begin to learn from these photos is that the evil behind the darkness and evil they portray is still resident in the hearts of those who try to motivate and direct us to resent, oppress, and hate and lay blame upon specific groups and people for whatever purpose they are hiding behind their overbearing pride, self-sanctity, and evil speech.

And it is this that we must resist, condemn, and fight against, remembering what we saw and understood from the faces, and especially the eyes of those children we looked into, in their last hours and moments. How else are we to love God with our whole heart, mind and soul, and our neighbor – those created in the image and likeness of God – as ourselves – and not as we love ourselves, but as if our neighbor is ourself. This is the only appropriate and meaningful response that could possibly fill our hearts and minds – a profound response to the evil murder of men, women, and children to which we must whisper and shout, “Never again” for any group of people.

Micah 6:8

He has told you, O man, what is good;

And what does the Lord require of you

But to do justice, to love kindness,

And to walk humbly with your God?

***

To view “The Auschwitz Album” Home page from Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, please use the link below.

The Auschwitz Album | Yad Vashem

To read my book review of “The Auschwitz Album” and “The Last Album – Eyes from the Ashes of Auschwitz – Birkenau”, please use the link below.

To view another posting where I write of my granddaughter that Naomi so reminds me of, please use the link.

To View all My Postings on Ukraine, Please Use the Link Below

Ukraine — Friends, the War, & Hope – Writing In The Shade Of Trees

To view all posts in the Moments of Seeing & Occasional Pieces, please use the link below.

Moments of Seeing & Occasional Pieces – Writing In The Shade Of Trees

This was really sad. Heartbreaking. I cannot understand people who deny the holocaust. I heard Eisenhower was the one who ordered pictures taken after the war. I heard he said he wanted to provide proof. Because of him, we know it was not made up. The hatred of Jews must stop. My cousin’s daughter is half Jewish. She is in law school. We love her and are so proud of her! I have four family relations now who are lawyers! My nephew Chris and his wife, my two brothers in law, and now Marisa who will soon be one! He is good.